What's Getting in your Way?

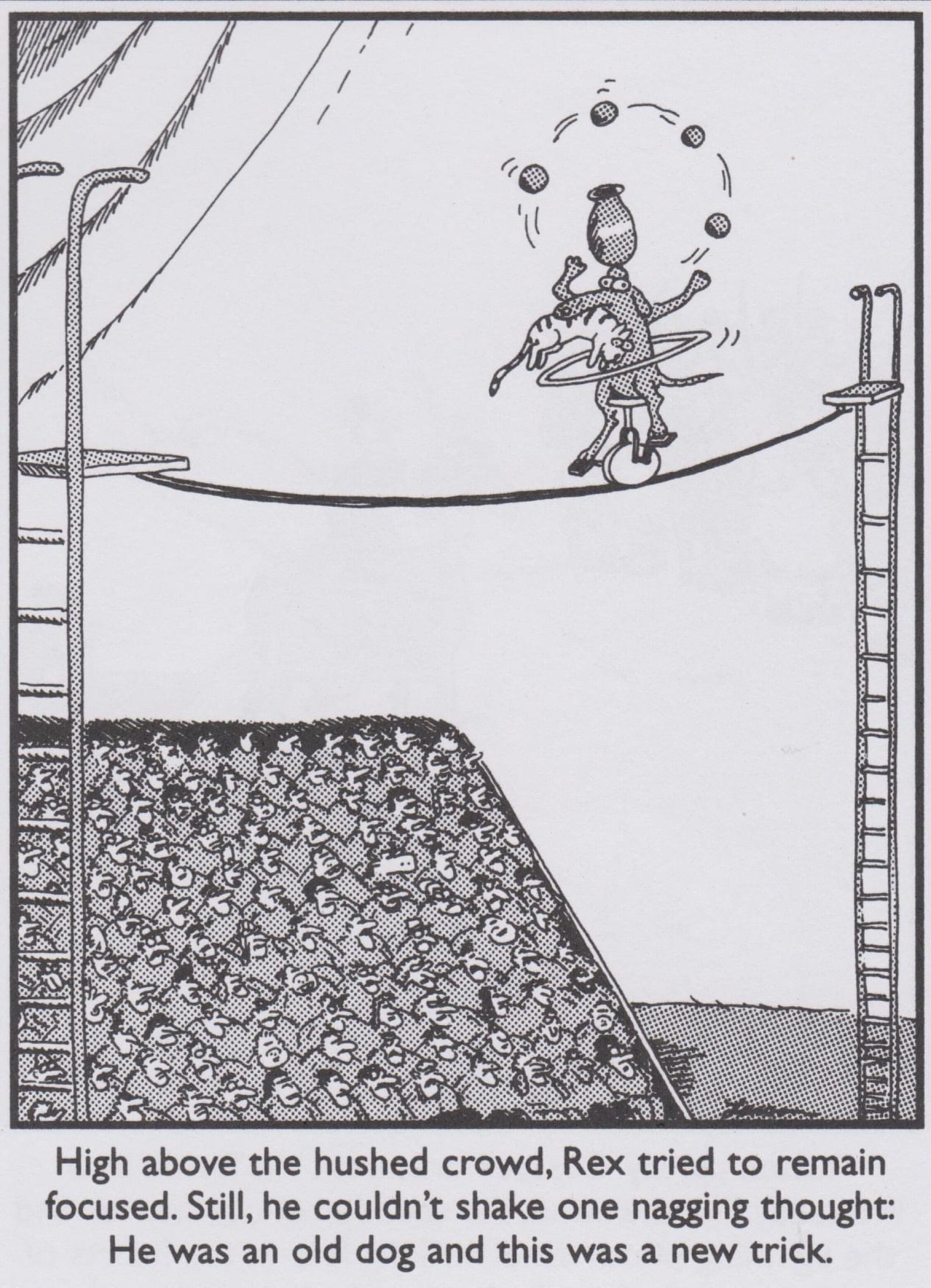

Many of us labour under the misapprehension that we essentially just need to work out what is best for us to do, and then we’ll simply do it. I find it fascinating that parents (and schools) will look at children, and observe “poor” time management skills, the “inability” to prioritise, difficulty “focussing”, and often expect rather “better” of them, very much on the basis that if the “good habits” aren’t instilled young, they’ll have no hope as adults. I put all of those things in quote marks because those are all judgments, coming from a particular paradigm of how learning should happen, and maybe there’s lots of good stuff happening while the maths homework sits waiting until the past panicked moment.

My point is that our expectations of how easy it is to instil habits - in either the young or the more mature - is at great odds to the reality of how much people struggle to incorporate changes into their lives. There are so many books on the subject, so many podcasts, so many courses. Every year so many people use the resetting of the calendar to have another go at self betterment. And whilst some people do make habits stick and do feel that they are generally on an upward trajectory to where they want to get to (and these people are often Upholders and Questioners on the Gretchen Rubin Tendency scale), many people really struggle and even those that manage it, often don’t find it easy. Gretchen Rubin has also identified twenty one strategies for habit change. Twenty one! If one strategy worked for everyone, there wouldn’t be the need for so many. And it was always thus. It isn’t necessarily a modern day phenomenon (although maybe the bids on our attention are greater): Aristotle was writing about it back in the day - and that day was hundreds of years before the Common Era. “Virtues are formed in man by his doing the actions,” he said. This has been interpreted as: “We are what we repeatedly do… therefore excellence is not an act, but a habit.” This very much reinforces our emphasis on small, sustainable and sustained habit changes over time.

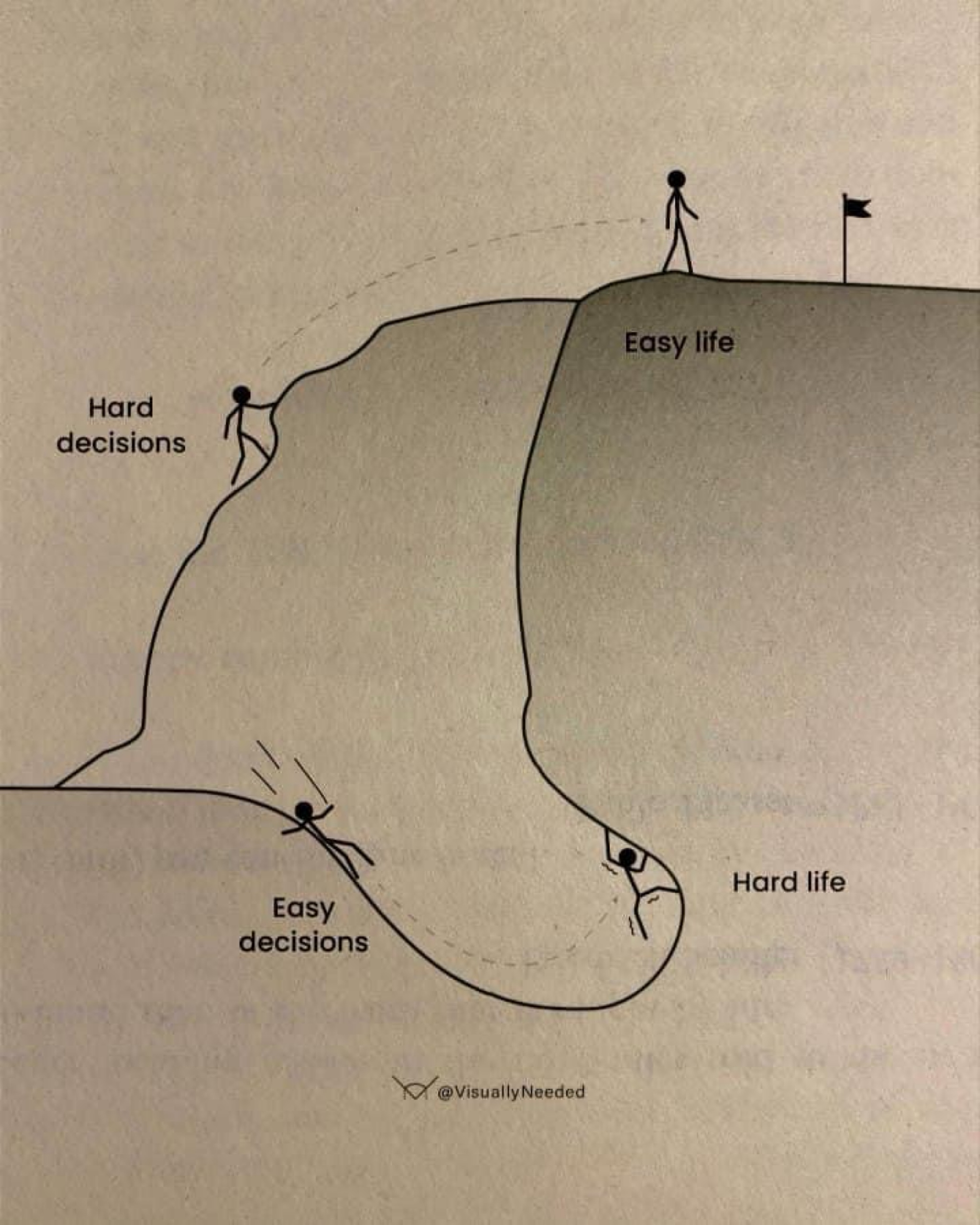

Very occasionally, there’ll be an abrupt trigger that causes almost instantaneous change. Usually, this is a pain point that the person want to move away from. You’re aware of the generally accepted paradigm that we are motivated by either moving away from pain or towards pleasure? It’s somewhat reductionist, of course, and you might not feel it captures all the nuances of human existence, but nevertheless there is great mileage in working out where the pleasure and pain points are, because it’s not always as obvious as it seems.

And this is another very important point: humans have large neocortexes, especially compared to many other mammals, and it’s the neocortex that enables the most complex mental activity that people associate with being human. I think it’s probably this that makes being human so complicated! And this is part of what makes incorporating simple life changes so difficult. There are so many nuances and considerations, so many influences on our decisions, and we have the ability to find some very plausible reasons why that thing we decided yesterday was such a beneficial thing to do is now not such a good idea.

Even now, as I am writing this, I have been questioning the decision I made yesterday to repeat an exercise segment today. Yesterday, I stomped briskly up the hill just opposite my house, for about a mile, and then I ran back down the hill, for about a mile.This seems like an excellent thing to do. It’s a beautiful route. Running downhill has been shown to be more beneficial than running uphill, counterintuitive though that is. See here. It only takes half an hour. I need to do this because I have a deadline for getting fitter (the Urban Combatives Instructor Development Programme, starting soon). I want to do it because the menopausal weight gain is not making me happy, and this is a good type of exercise to counteract that. It’s actually a nice day. It also meant I was warmed up and could go into doing a few weights when I got back, which is a big bonus, as warming up for those takes time. Really, there is so much in its favour, but there’s a big part of me that doesn’t want to do it. Part of it is the effort, of course - it’s only beneficial because it requires effort. And - a big one for me - it’s to do with how I feel about how my time is portioned. I have work in the studio later, and then training this evening, and this is my time to get on with Thorny Rose and other stuff. It feels like an imposition. Even though it’s a perfect break during a morning spent at the computer.

There are even more things I’ve been contemplating, but you get the point. Today is a day that I can do this, and tomorrow and the next day aren’t. Making the decision that this is what I am doing today and sticking to that decision is easier than negotiating with myself. It is true that I will have a fairly active afternoon and evening, but I need the extra session to boost my fitness. So with that in mind, excuse me while I go and get changed and head out the door. I’ll be back in half an hour!

[Some time passes….]

So of course, that utterly felt the right thing to do. And it was easier than the day before. It can’t be that my fitness improved by that much, but somehow the second time does always seem a bit easier. I’ll keep doing this extra snippet of exercise as often as I can, and since it won’t be daily, it makes sense to look in the diary and see when I plausibly can do it. Otherwise, we can fall prey to feeling generally guilty about not doing things without realising that we actually didn’t have much by way of opportunity.

The “moving away from pain” trigger to action often takes the form of a near miss. A scare. An insight into how things might be if we don’t take the action now to prevent bad outcomes in the future. And how powerful this trigger is often depends on how close we perceive that future to be! A young smoker might not look at an elderly person with COPD and see that as a dire warning. There is so much time between being young and being old that they will perceive, quite correctly, that it will be a considerable while before they experience such awful effects, and that they have plenty of time to change course. A long term smoker in their mid-fifties, on the other hand, might look at a seventy year old with COPD and think: “if I stop now, I could maybe avert that fate”.

A twenty year old smoker that wants to improve their time on a 10k run might feel the short term pain of lungs that aren’t functioning as well as could be expected. They might move away from that pain and towards the pleasure of getting a faster time. But this would mean they have to move away from the pleasure of their addictive habit and towards the pain of stopping smoking. As I say, it can all get a bit complex and maybe a bit confusing.

So there are a couple of things at play here. The motivation, the “why”, and the barriers to achieving the goals associated with that “why”. Being really clear on the “why” is a crucial part of initiating and sustaining lasting change. We’ve looked at this briefly already with this article “Find your Why”. A general sense of “I should probably do this because people say it’s good for me” is unlikely to survive contact with the first dark morning. We might have been certain that we wanted killer abs and a “beach body” and then reappraise that motivation as “vain” or “shallow” when faced with a challenging core workout. But even when our reasons for certain goals are crystal clear, and we feel super motivated, there are still barriers to that achievement to be overcome.

Identifying these ahead of time allows us to develop sensible and workable strategies around them. This can really make it so much less likely for a new habit to be derailed before it’s even really established.

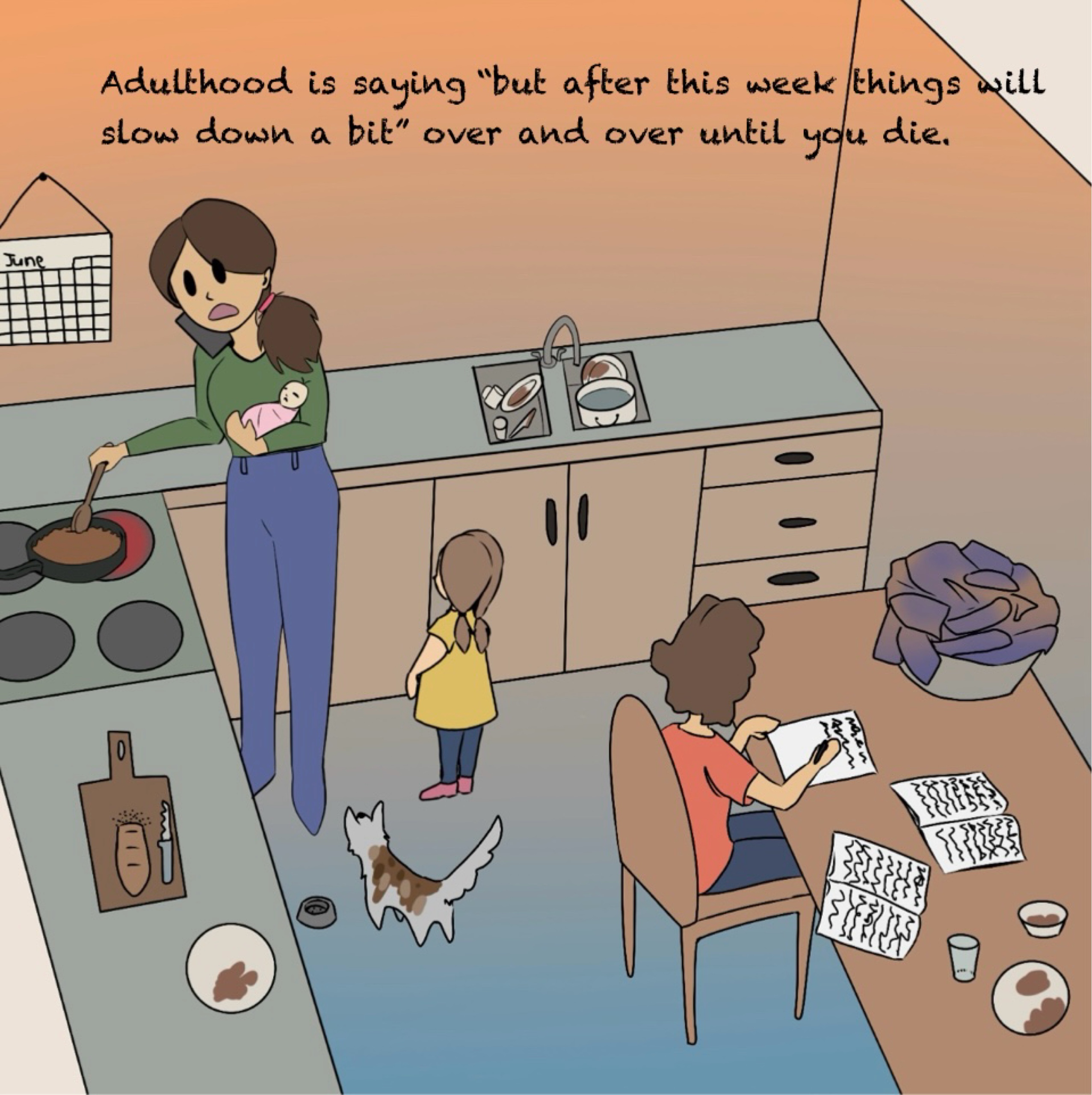

It’s likely we have some barriers or challenges in common: for most women, not having enough time is the one that comes up most often. But it’s more complex than that, and worth exploring.

It’s worth looking at internal and external barriers. And it’s also worth differentiating between change we can make that only depends on us, and change that depends on someone else, too.

So we’re going to delve a bit more deeply into these three areas. Finding your why, identifying the barriers, and then (a little later) setting goals. This is a bit of a circular process. If we only have 20 minutes a day available to us these days, we aren’t training for an ultra marathon. And once we’ve worked out what we want to do, there might be barriers particular to that ambition. And we aren’t going to be able to embrace any change if we have some deep rooted objection to doing so! But as I say, we get more than one pass at this. In fact, we get as many as we need.

Ready? Let’s go!

If you’ve had a chance to do any of the exploratory exercises this week, there have some been some invitations to make some lists!

First off is to make a list of your whys. I have been writing about some of the amazing benefits of exercise, and that might provoke some motivation, but this isn’t just about the exercise. It’s about the embracing of vivacious health, appreciating how wonderful we can feel. I’m trying to avoid phrases like “fulfilling our potential” because growth isn’t always about achievement, and it’s not necessarily about the things we can do. It is about having choices, though. Poor health definitely reduces our options. But whatever your reasons, they have to resonate deeply with you. Take some time to write them down. Why are you committing to Project You? What do you want to gain? And lose?

I don't know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn't everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

With your one wild and precious life?

Mary Oliver, The Summer Day, excerpt.

Once you’ve done that, the next invitation is to write down what you can easily identify that can get in your way. This is more on a practical basis. Such as “I’d love to join a running club on Wednesday evening but that’s when my kid has their swimming lesson, I wonder if my partner could take that on? Or could I go for a run while they have their lesson?”. It might be that the latter doesn’t meet your needs. Yes, you’d get a run in, but you wouldn’t have the support and encouragement of the club.

This may be a shocking and controversial perspective, but….. I believe that your needs are at least as important as anybody else’s. Maybe even more so because you carry so much. I also don’t believe it does kids any good to see their parents - especially their mothers - abnegate their own needs so fully.

It may be that when you look at the list of the barriers you understand how difficult it has been to prioritise your own health and well being. One of the simplest (not easiest) ways to deal with the barriers is to remove them. See if you can take that task off the list entirely. Or give that job to someone else. This is easiest done with a supportive partner and/or plenty of spare cash, but maybe it’s a question of creative thinking, and working with other women in similar situations. I know the notion of sharing responsibilities for lifts isn’t exactly original, but there are good ways to pool resources and free up time and mental space. We’ll look at more strategies for implementing change in due course.

The physical, practical barriers are only one part of the issue, though. Very often we have unexamined blocks that are getting in the way. The last listing exercise of the week is designed to get at some of those. It’s very simple. Choose a “thing” that you’ve been wanting to change for a while and that you think you are ready for. State that you are willing to do that thing in a simple way. It could be something very specific: “I am now willing to exercise for 20 minutes a day” or more broad: “I am now willing to embrace a healthier lifestyle”. Probably the broader, the more objections you will generate. This isn’t about goal-setting as such, so it doesn’t have to be SMART. If there’s been something you’ve been saying “I really must….” about for a while, that could be a good choice. Then without censoring, come up with as many objections as you can against that. Try to find at least 20, 50 is better. All the reasons why you don’t want to do the thing that you said you were willing to do.

I have done this around money - so a broader topic, around welcoming abundance and prosperity into my life, and more specifically, around birthing my daughter, who was a bit “overdue”.

In both cases, there were a whole load of fairly obvious objections that I was already aware of, and then one “ohhhhhh” moment. Clearing that objection is like moving a stick blocking a culvert - suddenly a huge amount of flow is released!

This exercise could be done around applying for a promotion, starting a business, giving something up, taking something up, and it could be done pre-emptively to smoke out prospective objections, or in response to a feeling of bafflement that something just isn’t changing.

Have a go. I really recommend it. And let me know if there is anything you would like to share, or questions you want to ask.

It's worth "smoking out" limiting beliefs!