Find Your Why

Making and keeping new habits is something we often, as humans, find very difficult. It’s easy on paper, and we can start off very motivated, but we can quickly lose resolve, or life just gets in the way. We don’t always consciously decide we can’t be bothered to do some exercise, we just get to the end of the day and realise that we didn’t manage to fit it in, often through no fault of our own.

Years ago, I read a book by Dr Phil, of Oprah fame, called Stop Making Excuses, and it was essentially just about that. It wouldn’t be everyone’s cup of tea, but even now, when I find myself wavering on something, I ask myself “did I commit to this, or not?”, and very often that’s all I need to kick myself into gear. Sometimes, the answer is “no, actually, this doesn’t mean as much to me as I thought”, and that’s good, too. Knowing what not to commit to is surely just as important.

If habits were easy to install, there wouldn’t be countless books on the subject, stretching back centuries. Even Aristotle had this to say:

“We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, therefore, is not an act, but a habit”.

I also thoroughly recommend Gretchen Rubin on this topic, and I will refer to her work quite a lot throughout this project.

What does make it easier is having a clear sense of “why”. A vague notion that we ought to be doing something, or an idea that something is “good for us”, is often not meaningful enough for us to establish a sustainable relationship with that habit. If we aren’t clear on our “why”, we can often find ourselves questioning what we are doing, whereas when we are really clear on the reasons we are doing something, we can just sidestep all those questions and get on with it. Doing a bit of work up front can free us from the ongoing decision-making that is actually really tiring.

There’s a difference between finding your why, and the strategies that might help implement it.

A why is not the same as a goal. It’s the reason behind the goal.

For instance, your why might be to not end up with poor posture and aching knees and weak bones and muscles when you are older. That can be a very compelling reason. It’s definitely part of my motivation. You can be very clear on that, but as a goal it’s not stated in the best possible way. There’s a whole section on “well-formed outcomes” to delve into this.

A why can be curiosity based, too. “I’m doing this because I want to see (how much muscle I can gain in a month if I really try/what happens if I cut down on sugar)….”.

Things which are deadline driven are often easier to stick to. For me, examples have included pregnancy yoga, or hypnobirthing. The impending birth is not negotiable, so preparing for it is top priority. Or more recently, Urban Combatives weekends - being fit and strong and mentally able to endure the physically and emotionally challenging content isn’t something that can be done last minute. For athletes and competitors, the schedule is obvious prior to an event. You might want to join a dance class that starts next term, and get a little bit fitter ahead of that. All of these considerations make it substantially easier than just a vague lifeline stretching out ahead of you in which “healthier” somehow features.

Another strategy can be to set a timeline, rather than a deadline, for giving something a good trial. I haven’t been absolutely convinced that the breathing and cold water exposure that Wim Hof advocates is really all that, so I’ve said to myself “let’s give it a go, to the end of the year, and see if we notice any changes”. The end of the year in this case will have been about 3 months, plenty of time to try something out. I also have the additional motivation of preparing for a big UC mindset seminar in December, and I will draw confidence from knowing that I will have done, by then, 70 days in a row of cold water exposure, and breathing. As I write, I’m on day 45. It takes away all the decision and uncertainty. I don’t have to ask myself “should I do this?” because I have already said I will (unless I am properly unwell, it’s always good to define the “unless” clause ahead of time). There’s no point in asking “do I feel like doing this?” because getting into very cold water is not in itself something I would naturally feel motivated to do, especially given that I do it in the mornings, and it quite often involves disturbing the cat that’s settled on my lap.

In the process, of course, it turns out this is making me feel very well. It seems unlikely I will want to stop anytime soon. But do I want to do this every day for the rest of my life? Probably not. So currently my thought process is that I’ll stop doing it in the summer, when keeping the water cold is a faff, and have it as an autumn/winter/spring thing, probably for a big chunk of the rest of my life.

And exercise is like that. Are you going to do exactly the same routine/workout for the rest of your life? Or are there going to be fluctuations and changes? Will you go a bit more intensively at some times and back off at others? Most likely, yes, and that’s more than fine. It’s better to ring the changes, to prevent some of the habituation issues (more on that later), and also to allow for the times when you are more into it, or less so. The circumstances have to be somewhat exceptional for zero exercise to be the best option, but a cycle of intensities is not a bad thing.

“Exercise” is amazing for our physical and mental health, on just about every level. It’s almost like our body and minds need to move. The benefits are countless (see “what is exercise?” For more information). That in itself can be enough of a “why”, but it’s still worth investigating. What is your real reason for doing this? You might find it changes as you go along. I’d like to suggest a valuable “why” is that this is a significant form of self care, and self care is how we retake our power. Or that we can get so much more enjoyment out of our lives if we are fitter and healthier, and extend our “health span”. Maybe there’s an activity you would really like to do, but you need a better weight to strength ratio to start it.

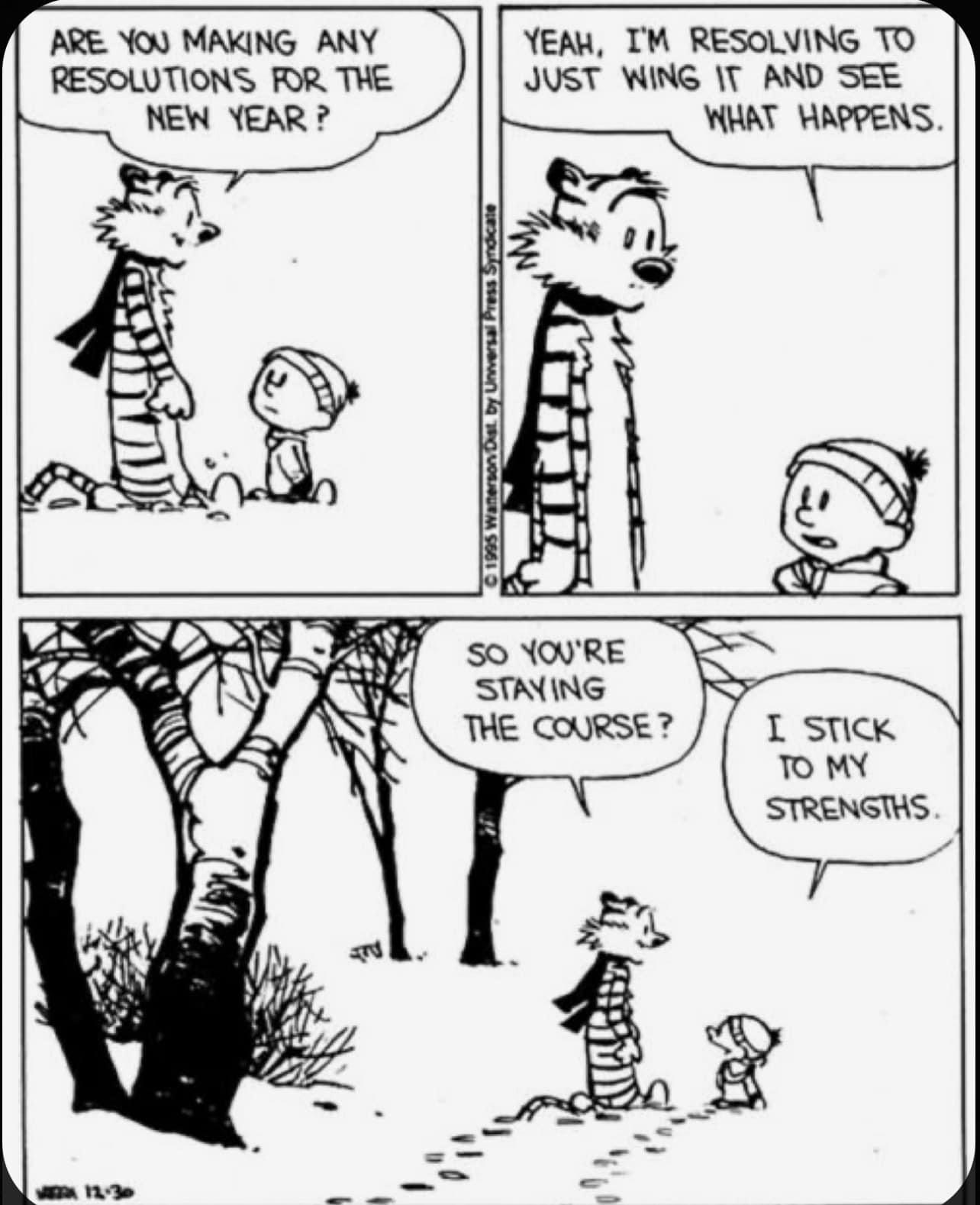

There’ll be more opportunity to dive into this area as we progress on through, so don’t worry if your why isn’t super clear to you. You can bypass some of that and just commit to turning up every day for yourself and seeing what happens. Let me know if you find yourself struggling to find a “why” that resonates, or if you find your commitment wavering.

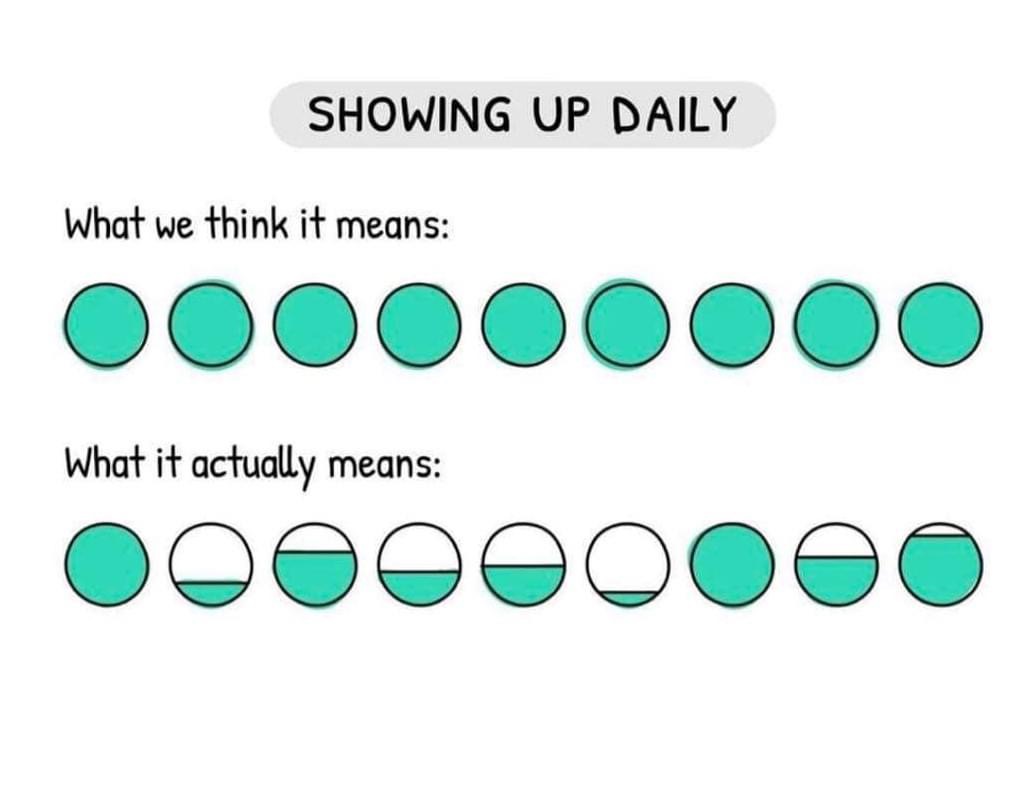

Having said all that, we sometimes need more than one run at something. Life can get in the way and good intentions can fall by the wayside. It’s life. What’s important is keeping the door open to return to what you know is of value, and coming back to it when you can. All or something is better than all or nothing.

I think this sums it up quite well (although why they chose nine days is mysterious to me).

[I can’t attribute to an author as not signed].